December 02, 2013

Design Lead John Won went to India twice as part of IDEO.org's project with World Health Partners to streamline data collection in telemedicine.

After doing several projects with IDEO.org, I’ve come to realize that there are three things (and a ton of ideas) that I need to take with me when I head into the field.

1. Printer. Ink. Paper.

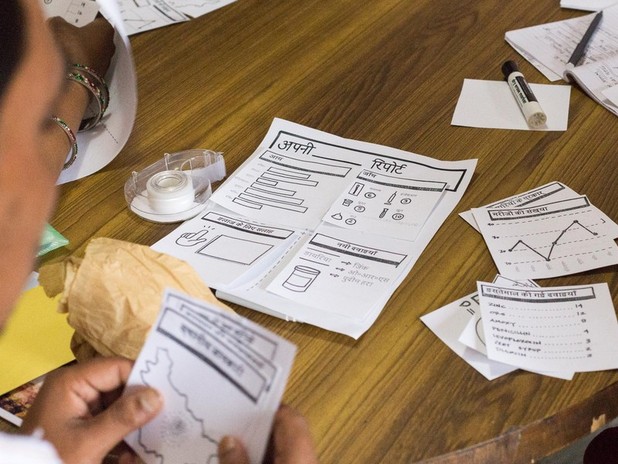

If design is about making stuff, human-centered design is about making stuff happen. Turning ideas into something visual and tangible is key. And the ability to do so in the field is critical if you’re going to create and iterate on the fly. What this actually looks like can range from marker sketches to illustrate sacrificial concepts to building a 20-minute prototype to test a simple hypothesis like whether business cards are valuable for informal workers. This requires bringing—or finding—the right tools. For a communications designer like me, this means a printer, ink, and paper. Maybe also a battery.

At IDEO.org, we've got a few portable printers that we pack on trips. Extra ink, paper (of different stocks and types), and USB cables help ensure you don’t carry that extra five or ten pounds into the field just for the cardio. You can even add a battery pack for some printers to deal with spotty power grids. We rely on them so much that designer Danny Alexander even fell in love with his little printer.

And then there are scrappier alternatives—scissors and paper, printing in a hotel lobby, internet cafes, or local service bureaus and print shops that are increasingly common in big cities in the developing world.

2. Network Like It's 1999

I'm used to opening my laptop, keeping a hawk-like eye on my email, watching Google Docs and Dropbox spin to life, and then, in a few seconds I'm ready to work. Wi-Fi is now a baseline requirement in San Francisco, but in peri-urban and rural Bihar, India, the all-pervasive Internet is often nowhere to be found.

A broadband dongle that plugs into your laptop is a lifesaver—and on a recent trip our partner World Health Partners lent us one—but that can still be slow and inconsistent. I need to stop thinking in megabytes, start thinking in baud, and relearn to love dial-up.

First coping mechanism: I turn off any apps that suck down bandwidth. This includes any webpages with ads and lots of images to load.

Gmail becomes "Simple HTML" Gmail. It's not as easy or streamlined as you might think.

For sharing documents in the field, I switch off Google Docs and Dropbox, since cloud-based apps stop working consistently or at effective speeds. Instead, I rely on Evernote (pro tip from former IDEO.org designer Robin!). It creates "notebooks" of content that it stores locally on your device and syncs to the cloud—when there's reception—enabling sharing with team members. Most importantly, Evernote doesn't stall when the Internet goes down so I suffer many fewer spinning beach balls and sad-faced web pages.

3. Pics, or It Didn't Happen

My smartphone's wireless data is usually switched off when I'm in the field (roaming fees kill). But I still use it to check notes, archived emails, or to take the occasional embarrassing pic of a team member— a must for morale =D.

For the shots that I don't want to miss, I bring out my DSLR. Lugging one around does come with overhead, however. It can intimidate or distract subjects and it requires more fiddling with controls and settings than the average camera. Also, it's harder to pack, attracts more attention in crowds, and has a higher profile for theft. But it's worth it for the photo quality and speed, low-light performance, and the great depth of field.

The trickier question, and one we’re always grappling with, is knowing when to shoot and when not to.

Ascertaining the comfort level of a subject and asking for consent is critical. In India, Minnie Bredoux shared her golden rule of always—always—asking people’s permission before photographing them. It’s a good reminder and a critical reflection on how we act in the field. In places like Ghana, many people will yell at you for taking photos—at times even at the slightest hint that you might take a photo of them. Last year, one man remarked to a colleague that he was tired of tourists and NGOs portraying Africans as desperate and destitute. That kind of representation has a name in our biz: poverty porn.

So, here's the question: How might we take this man's complaint as a prompt for design? How do we show the reality of a place without taking away the dignity of its people? How do our Instagrams and Vines and Flickr streams capture not just grit and need, but also agency, resourcefulness, and optimism?

Maybe the best things to take into the field are awareness, mindfulness, and self-critique.