January 23, 2013

IDEO.org Fellow Matteo Signorini has spent six years as an IDEO designer. Now, after five months on the job as an IDEO.org designer, Matteo reflects on the differences of what it means to be a designer in these two worlds.

As an IDEO designer for the last six years, I am used to doing user research in "developed" markets, where we often visit users in their homes and talk with them about their life challenges and aspirations. We talk to them about interacting with brand new technologies, that we then put in their hands in the form of prototypes.

Now, as an IDEO.org Fellow, I am doing similar research, but in developing markets. How is it different to do the same work with the bottom of the pyramid? And when the technology is a squat toilet?

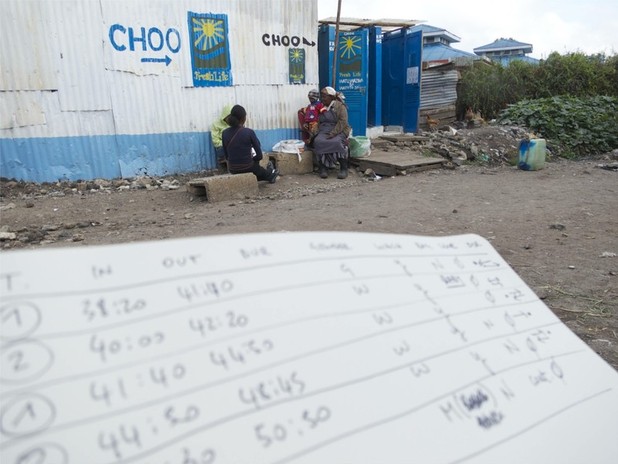

I spent two weeks in November in Mukuru, a slum in Nairobi, Kenya looking for opportunities to increase toilet adoption in this informal settlement. We were working with Sanergy, one of our IDEO.org Innovation Fund partners, on their toilet franchise model called Fresh Life.

For five days in a row we spent every morning in the muddy streets of Mukuru (it was rainy season in Kenya), observing the morning rush hour on the streets and meeting with local people in their homes and businesses. We learnt about their daily frustrations, habits and choices. We also learned a great deal about the motivations and challenges facing local Fresh Life Toilet operators. We even tried the Fresh Life toilets ourselves.

On the long flight back to San Francisco, I spent some time collecting my reflections from my first research trip to Africa. Here are a few of them:

Forget recruiters, forget interview appointments

In my days as an IDEO designer, we spent a lot of time at the start of a project looking at interview participant profiles and finding the right recruiting agency. This is not how things are done in the developing world. In Mukuru, we started our research with a translator from the neighborhood and interviewed some of his acquaintances. We asked for leads for “somebody who spends the day around here, but does not use the toilet in this area regularly." Off we’d walk to meet someone who knew someone. Knock on another door or enter a different shop across the road, where we would be introduced to a new person. After each interview in Mukuru, we quickly discussed the user profile of the person we’d just spoken with and then briefed the translator on what type of profile we needed next. It's a time consuming process, but you get to know the area and the people. And needless to say, there were no recruiters involved.

Embrace the group interview

A basic rule of human-centered design research is to “always interview in context, so as to create empathy.” In many instances, we try to do interviews in people’s homes. In Mukuru, this often wasn’t possible and we conducted many interviews on the street. This meant gathering a natural audience to the conversation, which can change the tone and the answers of the person being interviewed. When such a public interview occurs, you have two choices: either you can convince the participant to invite you to their home or someplace more private, or you make the best of the attention and engage the crowd in a group survey.

Open questions are lost in translation

When working in a community like Mukuru in Kenya, our questions have to go through several translations (from English to Swahili and often to Sheng - the local slang). Our questions are also passed through different levels of education and different cultures (interviewer, translator, participant). When conducting interview questions, we do our best to formulate open questions (WHATs, WHYs and HOWs) to stimulate conversation and get our interview participants talking freely and giving their opinions. However, when dealing with translation (and translation of translation), the answers to our questions get shorter and shorter with each additional step in the communication process.

Spend time on your prompts, not on the questions (and be ready to draw a lot!)

After years of experience, we IDEO designers know that a visual prompt (such as a simple drawing) can be much more effective at stimulating reactions from interview participants. When interviewing in a place that has language and cultural differences like Mukuru, the importance of the visual is even more profound. So I began visualizing every question we asked as a comic illustration on a notecard. And then we began drawing the questions. It took several interview sessions to refine our illustrations and avoid misunderstanding (we went through a lot of notecards!), but when the process was complete, it got us to faster insights and let us compare opinions from different participants much more easily.

We stick out, whatever!

In my career as an IDEO designer, I’m used to sitting in hospital waiting rooms or bank lobbies and observing people. As part of our project in Mukuru, we did a similar observation, taking several hours to observe customers in front of Fresh Life toilets, to get firsthand data on actual usage. We attempted to be very discrete and believed that we had disguised our observations. Afterward, during our conversations with Fresh Life operators and users, we learned that many people had discretely asked, "Why are these ‘wazungu’ timing us in the toilet?" Muzungu (or Wazungu for plural) is the Swahili word for foreigner.

Post-its don't stick on every wall

This one pretty much explains itself.

Looking forward to the next field research trip!